Growing and selling marijuana is a labor issue, not just a legal one. In one union, that means corruption.

On September 17, Daniel Rush, an organizer for the United Food and Commercial Workers, was indicted in Oakland by a federal grand jury for bribe-taking, attempted extortion, honest services fraud, and money-laundering related to his receipt of over $500,000 in cash and other things of value from marijuana dispensary employers in return for giving information to the employers on how to defeat union campaigns.

Arrested on August 11 following a lengthy FBI probe, Rush pleaded not guilty to all charges on September 23. A spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of California told NLPC today that a status conference is set for December 14.

Arrested on August 11 following a lengthy FBI probe, Rush pleaded not guilty to all charges on September 23. A spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of California told NLPC today that a status conference is set for December 14.

Over the past couple of decades, and with gathering speed, attitudes in this country toward marijuana have evolved in a libertarian direction. We’re now well beyond the time when possessing a half-ounce of marijuana could be a ticket to jail.

Back in the 1930s, the federal government enacted a series of laws that outlawed the sale, possession and use of that substance. Marijuana quickly became devil weed in the public mind, thanks to its being outlawed and to a misleading information campaign whose most noteworthy artifact was “Reefer Madness,” a film whose preposterousness ultimately led to cult status.

As usage became widespread during the 1960s and 70s, pressure to decriminalize or legalize marijuana grew. The last several years have seen an acceleration of this trend, despite the continuing hard prohibitionist line of the Drug Enforcement Administration. Several states – most dramatically, Colorado – have legalized the drug outright. Many others have decriminalized it or allowed it under controlled medical conditions.

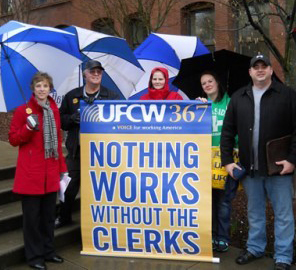

With the marijuana industry sprouting above ground, workers have begun to organize for better wages and benefits. One union, the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), hears opportunity knocking. The UFCW, in fact, for several years has had its own medical cannabis division. And it’s achieved results. This June, workers at the Cannabis Club Collective, a Tacoma medical marijuana dispensary, unanimously voted to join UFCW Local 367.

“We’re going to set a high bar for our industry with a contract that’s fair to both workers and owners,” said a member of the union bargaining committee. Making the organizing possible was Washington State voter approval by 56-44 percent in November 2012 of Initiative 502, which gave eligible medical patients of at least age 21 a right to carry up to one ounce of marijuana and grow up to 15 marijuana plants.

In Ohio, meanwhile, the UFCW and a nonprofit group, ResponsibleOhio, campaigned this year to put a constitutional amendment on the ballot, Issue 3. The measure, defeated by 64-36 percent, would have legalized marijuana, but also granted 10 growers control of all marijuana production in the state.

One potential grower and backer, equity fund manager Woody Taft, explains: “Over the course of history, owners of these businesses have taken advantage of these workers, and we want to be clear that we’re not going to do that. We’re going to give them a fair wage and fair benefits.”

There is irony here; Taft is a descendant of U.S. Senator Robert Taft, the driving force behind the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which reined in certain union excesses. Marijuana is big business. And organized labor wants a piece of the action – in one case, too big of a piece.

That brings us to Daniel Rush, who, until his recent termination, had been chief organizer for the United Food and Commercial Workers medical cannabis division since 2011. Before that, he had been an organizer for UFCW Local 5.

According to the FBI and federal prosecutors, Rush, 54, a resident of Oakland, illegally used his position as a union organizer during 2010-14 to obtain money and other things of value.

Rush allegedly engaged in a scheme by which he would receive forgiveness of $550,000 of a $600,000 loan from a representative of area medical marijuana dispensaries, and in exchange would give the dispensaries favorable treatment. It was classic quid pro quo: A union official or worker enriches his bank account, while the employer remains nonunion. The type of arrangement long has been illegal under the Taft-Hartley Act. Rush, for his part, was unaware that the industry representative was cooperating with the FBI.

The indictment alleges several additional allegations. First, Rush accepted financial kickbacks from an attorney to whom he had referred the dispensaries as clients. In so doing, he committed honest services fraud against dues-paying UFCW members.

Second, Rush, as an officer of a nonprofit low-income group, Instituto Laboral de la Raza, allegedly took kickbacks from the attorney in exchange for having him represent clients in workmen’s compensation cases. He steered clients to the lawyer; in return, the lawyer provided Rush with a credit card on which Rush charged thousands of dollars of personal expenses – all paid by the lawyer.

Third, Rush, as a member of the Berkeley Medical Cannabis Commission, a city agency that licenses and regulates medical marijuana operations, demanded a well-compensated job from a prospective dispensary. In return, he would use his position on the commission to provide the dispensary with favorable treatment. This arrangement constituted extortion, noted the indictment.

Fourth, Rush allegedly participated in a money-laundering and financial structuring conspiracy to conceal the origin of the $600,000 loan. The U.S. Attorney’s Office press release clarifies: “Rush and the attorney engaged in a series of structuring transactions designed to obscure the origin of the money.” Rush, the release continued, “required the attorney to fund interest payments on the loan and, when Rush ultimately was not able to repay the loan, he offered favorable union benefits in exchange for forgiveness of the loan.”

After his August 11 arrest, Daniel Rush was fired from his $121,124-a-year UFCW position and indicted on September 17. Six days later, he pleaded not guilty to all charges. William Osterhoudt, a public defender, puts it this way: “This treatment of Mr. Rush is entirely unjustified. He has given the better part of his adult life to the union movement and has served the UFCW honorably for many years.”

The details of the charges suggest, however, that Rush has a tough job convincing a jury of as much, should the case go to trial. If convicted, he faces up to 20 years in prison and a fine of up to $500,000 in addition to appropriate restitution. Marijuana legalization has its side effects, not all of them good.

Leave a Comment

COMMENTS POLICY: We have no tolerance for messages of violence, racism, vulgarity, obscenity or other such discourteous behavior. Thank you for contributing to a respectful and useful online dialogue.